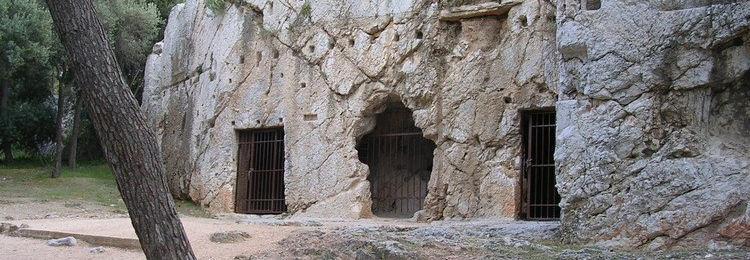

After the events of the Apology, Socrates awaits his execution in a prison cell. His friend Crito, who previously (and unsuccessfully) tried to pay for Socrates’ acquittal, arrives to try and persuade Socrates to escape. Though Crito’s arguments are persuasive, and he makes clear that escape would be a relatively safe and sure option for Socrates to avoid death, Socrates refuses, claiming that ‘justice’ demands that he face his own demise instead. Is Socrates mad? Read on to find out…

After the events of the Apology, Socrates awaits his execution in a prison cell. His friend Crito, who previously (and unsuccessfully) tried to pay for Socrates’ acquittal, arrives to try and persuade Socrates to escape. Though Crito’s arguments are persuasive, and he makes clear that escape would be a relatively safe and sure option for Socrates to avoid death, Socrates refuses, claiming that ‘justice’ demands that he face his own demise instead. Is Socrates mad? Read on to find out…

Crito digested

Socrates: (to Crito): *yawn*, I just woke up. I’m surprised you managed to blag your way in here!

Crito: I’ve actually been here a while, Socrates, watching you sleep. I’m amazed that you’re so happy, given that you’re a man staring his own death in the face. Did you know that your execution is scheduled for tomorrow?

Socrates: Perhaps it is for the best… you know though, I had a dream in which a woman in white approached me, and suggested that it would be the day after.

Crito: Riiight… but whenever it happens, I cannot (as your good friend) just stand by to see you executed! I’m afraid that people won’t realise that Plato and I tried to bail you out with our offer of €70,000 … they’ll think we abandoned you! In fact, the majority of people would surely agree that you should be freed!

Socrates: Well who cares what ‘the majority’ of people think? Why should I be bothered with the views of the majority?

Crito: Never mind all that now! Myself and your other friends are prepared to sacrifice our money, property and safety to bail you out! Take our advice: let us help you escape. Don’t be afraid to ask: we have the money, and places we can take you where I have friends, and you’ll be safe.

Socrates: ….

Crito: (Angry and impatient) What are you waiting for?!? But hold on…. aha, I see. You don’t think it will be just for you to escape from this prison … well I say that it would! By staying here, you allow your enemies the pleasure of killing you, and you’re abandoning your sons to a life without a father. How could you?! You claim to be good and virtuous, but a good and virtuous man would come with us, and not take the easy route and lounge around in prison like you are. I am ASHAMED of you, Socrates, both for that pathetic attempt at a defence speech in the court, and your apparent decision to resign yourself to death. Give up this stubbornness, and come with me now, and out of here!

Socrates: Calm down! Let’s just examine what the right course of action is here, and go where the arguments take us. Let’s start with whose opinions we should value in this matter. Presumably we should value some opinions, but not others?

Crito: Well yes, seems so…

Socrates: So I guess we should value the good opinions, those of the wise men, and disregard the bad opinions, those of idiots?

Crito: Can’t disagree with that!

Socrates: Let’s be specific then: footballers, for example. Whose opinion should they value: everybody’s, or those of their coach?

Crito: The coach, obviously.

Socrates: Good, so a footballer should do what the coach tells him to, otherwise he’ll get injured on the pitch, or otherwise come to harm. I’m sure my favourite footballers, Socrates and Sokratis, would agree with me! And so it is with justice too: we should disregard the opinion of the majority, and focus only on the opinion of those we think the wisest; if we don’t, we will corrupt our very selves! The wise man is to our soul what the coach is to the footballer.

Crito: Ok, I’m with you so far.

Socrates: There we go then: all those people who say this or that about whether what I’m doing is just or unjust can be disregarded: we should only listen to the wisest people with regard to doing what is just. YOU said before that I should heed all those people who would bid me be set free, but we have a reason to ignore that majority now.

Anyway, let’s look at whether it really is just for me to escape from this prison, ignoring those things that the majority of people would think relevant: money, reputation, children and all that stuff you mentioned earlier. If we do establish that escaping is the unjust and wrong thing to do, then it doesn’t matter if I die or suffer as a result not not doing it! Because staying here was the right thing to do.

Crito: I guess I agree. But what is the right thing to do in this situation?

Socrates: Well, we can agree right away that we should never do what is wrong. And so we are never justified in doing something wrong in return for being wronged: that is, we can’t hit back or retaliate against somebody who has hurt us. The majority of people, on the other hand, say that we should retaliate! But they’re wrong. Not to compare myself to Jesus or anything, but, you know, I think he’d agree with this point.

Crito: Well, I agree.

Socrates: But DO you though? Do you really seriously believe this important point about harming a person being wrong, even in retaliation? Will you stick by it?

Crito: I will!

Socrates: Good. The question is, then, are we harming anybody by escaping from this prison? Well, let’s imagine we were caught during our escape by a policeman, who represents the Athenian society. Let’s imagine a conversation, which might go something like this:

Police: Stop right there! You’re completely ignoring the law by doing this! If everybody ignored the law, the whole of society would collapse!

Socrates: The city wronged me, so I am right to escape!

Police: Well you might be a bit cheesed off with your death sentence, but what you’re actually doing here is harming the whole of society by escaping! So ungrateful! You’ve been born here, grown up here, had a job here, made a life here… you’ve signed a kind of contract with Athens, you see, and with its laws, and you’re harming society if you break this contract, particularly in retaliation against your death sentence. You can accept the law, or you can persuade us to let you off (and you’ve already tried that one!) and that’s it. In fact, by trying to escape, you are extremely unjust!

Socrates: What? Why?! I never signed a contract!

Police: Oh yes you did. You chose to live here and benefit from this society. You were free to leave at any time if you didn’t like how it was run, but you didn’t: you stayed and made a living here! You had your kids here … you signed your contract with us, for sure. And then when you were sentenced, you could have pleaded for exile, but you didn’t! And now you try to run away, which goes against everything in our little agreement.

Socrates: Well, I can’t help but agree, actually. You have a point! I DID ‘sign up’ to live in this society, and am now being a hypocrite by unjustly acting against it.

Police: Damn right. And also, think about your friends. By breaking out of here, you endanger them. And you’ll be hunted down wherever you go, as you’ll have a reputation for being a lawbreaker, and your reputation will be ruined, even more than it already is! Will you go live in another lawless society instead, like where Crito’s friends live? I don’t think so. Your children won’t thank you for it: they’ll get no education, and be worse off. You’ll be known as an unjust man, and Hades won’t take kindly to THAT in the underworld when you get there! Better to ignore Crito, and stay right where you are.

Socrates: So you see Crito, in escaping with you, I would be acting unjustly, breaking my social contract, and therefore wronging not just you and our friends, but the whole of society. I won’t be persuaded on this!

Crito: I…… I….. I have nothing to say to this, Socrates. I can see that your mind is made up.

Socrates: Indeed it is, my old friend. Let it be this way: justice demands it.

More ideas

Is Crito right in arguing that Socrates is unjust by remaining in prison?

It may sound odd to argue that by escaping from prison, a person might be doing what is good and just, but this is precisely the view that Crito argues for in this dialogue, and he makes a persuasive case. Crito’s arguments concern the duties Socrates has to his family and his friends, as well as to philosophy as a whole: his argument is that in failing to take advantage of Crito’s escape plan, Socrates is giving in to his enemies, neglecting his sons, and allowing the state to triumph in its attack on the pursuit of virtue and wisdom, to which Socrates and his friends are devoted. The idea of moral duties was not new in the time of Plato, but has been influential in ethics ever since: Crito seems to be saying that we have moral duties to those close to us, and also to fulfilling meaningful goals in life, that may outweigh the dictates of the law. But Crito’s argument also leans on the consequences of Socrates’ escape: he doesn’t understand why Socrates is unwilling, given that he could in all likelihood make a safe and easy escape, aided by his friends. Crito also appeals to the ‘majority’: he says that many people would agree with him that Socrates is acting unjustly by giving up his duties to his loved ones and languishing in prison. But to what extent does the majority opinion matter when it comes to morality?

Does the opinion of the majority matter?

Socrates is very quick to dismiss the opinion of the majority, and favours instead a kind of ‘expert’ view on morality, where one’s moral action should be guided by those who are wise. This is a key theme in Plato, and anticipates famous discussions of justice and society in Plato’s masterwork, The Republic: the just society is the one in which the philosophers (those who are the wisest, and the experts on morality) rule, and the idea of a democracy (where the majority vote dictates morality) is rejected. We’ll return to this one again soon, when the Republic gets digested.

Socrates ‘social contract’ argument

Plato’s Crito is renowned for featuring an early version of the ‘social contract‘ theory of political morality, which later came to be associated with Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau. The idea is that by voluntarily living in a society, we form implicit moral and political agreements with that society (a ‘contract’), which form the basis of one’s existence. The idea that we owe something to the society in which we live is a common one, because it is often impossible to imagine our lives, with all their benefits and opportunities, being the same without the society in which they were made possible. For Socrates, the Athenian society made it possible for his parents to meet and marry, and for him to be educated and grow up to live a full life. Furthermore, this situation was not forced on him: Socrates could have left at any time, but didn’t. Breaking out of prison would therefore represent a violation of this contract, and therefore would be unjust. A further implication is that by breaking the contract, society is ‘harmed’, in a similar way in which a person is harmed when they are wronged, which Socrates and Crito agree can never be right.

Did Plato himself mean to approve of the social contract theory in this passage? And is the fact that it is attributed to Socrates suggestive that Socrates himself advocated the view? Probably not. In The Republic, Plato presents a rival view of justice as harmony of the soul. In this view, justice is worth having for its own sake, rather than (as in the social contract theory) having for the sake of an agreeable life in society and a good relationship with its laws. This is the big question: is justice merely a contract with one’s society, which would seem to imply that since each society has different laws, the demands of justice can vary, or is it something more objective and binding, independent of society? Given everything else we know about Plato, it’s almost certain that he would opt for the second if pressed. We shouldn’t assume, then, that everything Socrates utters in Plato’s work is a straightforward picture of Plato’s own views.

So, who is right? Socrates or Crito?

Both men make a compelling case, and their disagreement turns on where the most important duties of a person lie: with our families and friends, or with society? Crito proposes a view of justice which focuses on family and friends; in particular, Socrates’ sons. Socrates ignores this view, and focuses on society at large, offering a more impersonal view of justice. How these two views fit together, and which one we should prefer, is one of philosophy’s most enduring questions. By placing the demands of society over the demands of his loved ones, Socrates is satisfied that he will go to a virtuous death; but was this really the right thing to do?

Disclaimer

This dialogue has been abridged and re-worded, with some silly bits added, to make the key arguments more accessible and engaging. It doesn’t represent a totally accurate re-telling of Plato’s original (which can be read here). However, it is designed to preserve the key basic thoughts and arguments, as well as giving a sense of some of the fascinating philosophical issues that Plato addresses in this dialogue.

accept your demand to live a boring, quiet and obedient life,

accept your demand to live a boring, quiet and obedient life,

That’s right: you heard me. Just like Manuel in Fawlty Towers: I know nothing! But I’m very wise though. Perhaps the wisest in the land! You might think I’m boasting, but the Oracle at Delphi said I was the wisest, on behalf of all the gods. And if you don’t believe me, ask my mate Chaerephon. Well, actually you can’t do that because he’s dead … but anyway, ask his brother or something.

That’s right: you heard me. Just like Manuel in Fawlty Towers: I know nothing! But I’m very wise though. Perhaps the wisest in the land! You might think I’m boasting, but the Oracle at Delphi said I was the wisest, on behalf of all the gods. And if you don’t believe me, ask my mate Chaerephon. Well, actually you can’t do that because he’s dead … but anyway, ask his brother or something.

Socrates: Well the idea of an atheist believing in spirits is absurd, since as everybody knows, spirits are the children of the gods! Come to think of it, the idea of an atheist being spiritual at all is itself absurd! Just look at Richard Dawkins: he’s cold inside. And what about

Socrates: Well the idea of an atheist believing in spirits is absurd, since as everybody knows, spirits are the children of the gods! Come to think of it, the idea of an atheist being spiritual at all is itself absurd! Just look at Richard Dawkins: he’s cold inside. And what about